At a recent auction, we purchased a few Native American items from the former museum in Two Harbors, MN. Among them, this seemingly unusual combination: A Native American Peace Medal on an Independent Order of Odd Fellows (IOOF) collar.

This was not the only set; there were a total of three of these collar/medal sets. While one doesn’t normally think of Native Americans as Odd Fellows members, apparently it was a popular custom item in this area, anyway, for Native Americans to wear and display all honors.

The IOOF collar is beautiful in and of itself, with it’s decorated red velvet trimmed in twisted-metal fringe and tassels (one tassel is missing). The collar is secured by three oval chain links. The shape and materials date the fraternal cerimonial collar to the end of the 19th century. But the medal which hangs from the collar’s links is even more rare than the collar.

The medal is an Indian Peace Medals , presentation pieces to Native American or Indian chiefs as a sign of friendship. The series began as an idea in 1786, but were first produced during President Jefferson’s administration in 1801, with Jefferson Peace Medals designed and created by John Reich. Because the medals were given to significant members of tribal parties, the medals became sought after symbols of power and influence within Native American tribes and are commonly seen in Native American portraiture.

, presentation pieces to Native American or Indian chiefs as a sign of friendship. The series began as an idea in 1786, but were first produced during President Jefferson’s administration in 1801, with Jefferson Peace Medals designed and created by John Reich. Because the medals were given to significant members of tribal parties, the medals became sought after symbols of power and influence within Native American tribes and are commonly seen in Native American portraiture.

Most of the genuine Indian Peace medals awarded by the U.S. Government were made in silver and were issued holed or looped at the top, so the medal could easily be worn. (If a medal is not holed, and shows no sign of being looped, it is most likely a modern copy.) However, the Peace Medals were also struck in other metals, including copper. Starting around 1860, some of these were struck from the same or similar dies, for collectors. These copper pieces are known as “bronzed copper” because they do not look like copper coins. But given the popularity of the medals and the respect they conveyed, the Native Americans and traders also made or commissioned copies, in copper or silver-plated copper, of the Peace Medals too. These pieces are still over a hundred years old, yet even when produced by the US Mint, these medals are not considered “originals” as they were not awarded by the U.S. Government.

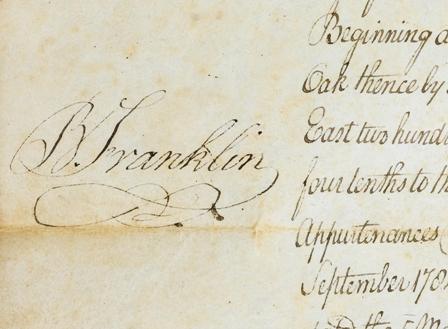

This specific Peace Medal is a John Adams Peace Medal, but it was designed and struck after Adams’ presidency. This medal does not appear to be silver, but, based on dimensions and weight, pewter. According to the Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico, Volume 1, edited by Frederick Webb Hodge (1907), a few of the Adams Peace Medals were struck in “soft metal” and these are “exceedingly rare.”

Our Peace Medal also appears to be the first design issued, as later variations do not have the fabric drape about the bust of the president, nor the year centered beneath the bust. The president’s bust on the obverse was designed by Moritz Furst, but the reverse is the same one the Jefferson medals. (This back design was used until the Millard Fillmore medals in 1850, when the reverse was changed. The reverse was changed again in 1862, during the Lincoln administration.) Interestingly, the Adams Peace Medal with the 1797 date was made later.

I’ve made some inquiries regarding this antique set and will update you as I learn more. Meanwhile, the set is in our case at Exit 55 Antiques.

UPDATE: In trying to find definitive information on this peace medal, I made multiple calls to auction houses and, per their recommendations, to companies which grade coins and other medals. Few seemed to know what I knew, or were willing to divulge what they did know about Native American Peace Medals. So I continued my research and then made a call to Rich Hartzog of AAA Historical Americana, World Exonumia. Rich seems to truly be one of the few people who knows — really knows — about Native American Peace Medals. I’d call him an expert.

During a phone conversation, Rich confirmed the “soft medal” version of this medal, but ours does not seem to be one of those. He clarified regarding the copper medals; while made for collectors, they are considered original peace medals — but are not presentation pieces given to chiefs and other leaders. And, finally, we determined that our peace medal is likely a more modern copy. It wasn’t just that the medal is made of pewter, but the fact that the medal is attached to the IOOF collar or baldric. Seems roughly five or six years ago someone began setting the copies of peace medals on these collars. Such medals still have a modest value; Rich says roughly $20-$40, compared to the hundreds and thousands of dollars originals bring.

While this may be a disappointment to hubby and I, I have learned a lot about peace medals — and learning is a huge part of why I love this business. I don’t mind admitting that I’m unsure of what I’ve found. In fact, I love researching, including asking people who specialize and know more than I do.

Last week Wifey and I were hanging out at our local antique mall when a woman came in wanting to sell a Tupperware full of bits and baubles. Among the jewelry and silverware was a small jewelry-sized baggie full of tokens. Although I’m no help when it comes to jewelry, Wifey was glad I was around to evaluate the tokens. As you may have noticed, money and money-like things are one of the things I collect. The baggie held some generic arcade tokens, a nice Sioux City transit token that went into my collection, a few southeast Asia Playboy Club tokens went into Wifey’s collection, but the rest were a variety of trade tokens.

Last week Wifey and I were hanging out at our local antique mall when a woman came in wanting to sell a Tupperware full of bits and baubles. Among the jewelry and silverware was a small jewelry-sized baggie full of tokens. Although I’m no help when it comes to jewelry, Wifey was glad I was around to evaluate the tokens. As you may have noticed, money and money-like things are one of the things I collect. The baggie held some generic arcade tokens, a nice Sioux City transit token that went into my collection, a few southeast Asia Playboy Club tokens went into Wifey’s collection, but the rest were a variety of trade tokens.

The soap coupon tokens I have are also rooted in an earlier type of token: the

The soap coupon tokens I have are also rooted in an earlier type of token: the  Coupon tokens did survive in some corners well into the twentieth century, particularly if you remember

Coupon tokens did survive in some corners well into the twentieth century, particularly if you remember

About the most unique thing about this bill is that it’s a

About the most unique thing about this bill is that it’s a