A few months ago I was driving down I-94, on my way back into town after a work assignment, and I got a call from The Wifey. She had gone to the Fine Arts Club‘s semi-annual rummage sale, and wanted to know when I would be home. She wanted to make sure I’d be back in time to go to the sale before they close, because my expertise and obscure knowledge was required. Never one to back down from a challenge, I knew I had better be back in time.

I made it with plenty of time to spare, and we got to the sale a few minutes before they were about to close. When I arrived, the lovely ladies of the Fine Arts Club, who had already briefed on my talents by my wife, were excited to hear what I could tell them. I was shown this small metal canister:

Everyone was all abuzz about this fabled expert in strangeness, and I wasn’t one to disappoint. I picked up the little container, turned it around in my hands, slid the little door open and closed, and made my assessment.

Everyone was all abuzz about this fabled expert in strangeness, and I wasn’t one to disappoint. I picked up the little container, turned it around in my hands, slid the little door open and closed, and made my assessment.

“I believe it’s a container that held nibs for fountain pens,” I proclaimed. ” See, they eventually wore out — you wanted to keep them sharp — so you had to replace them regularly. You bought a bunch of them at once and these came in this little tin. Usually the tin got tossed out I’ll bet, but this one managed to survive somehow.”

This revelation brought about gasps of “AHA!” and compliments to my wife on the accuracy of her claims of my ability to identify the little box. It had been brought in by a member to be sold, and it had been placed on the antiques table. Many customers had attempted to identify the little canister, but none had reached such a satisfactory description.

Of course, now that I had properly identified the artifact, I was, by their standards, the best possible customer to purchase the tin as well. I could certainly have declined, but I also felt the same curiosity and intrigue that the tin brought everyone else, so I negotiated the price down to $10, and took my new mysterious prize home.

Now, I may have shown an unshakable certainty at the rummage sale, but I wasn’t entirely certain of my answer. Nib packaging is still the best answer I have, but the name of the product made me more interested in the actual origins of the tin.

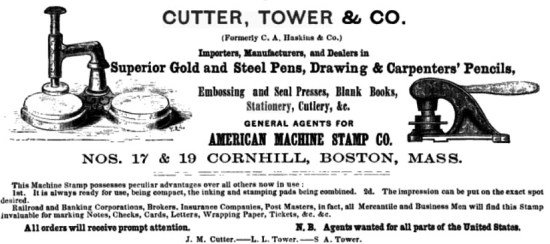

According to the tin, this belongs to the Atlantic Cable Pen, manufactured by Cutter Tower and Co. of Boston. It was patented in October 1856, and it’s identified as a No. 29 E.F., whatever that might be. It doesn’t give enough information to say whether the pen or just the tin was what the patent was for, and being such an early patent I could find no relevant patent from October 1856 in the online patent records. Cutter Tower and Co was an office supply and stationery distributor, who sold all sorts of writing implements, paper products, and other office equipment, often rebranded as their own. Still, the Atlantic Cable Pen eluded discovery.

The key to the tin came when I connected the 1850s with the atlantic cable — the Trans-Atlantic Cable, that is. Through the 1850s and 1860s several attempts to run a communications cable across the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean were made, with final success arriving in 1867. As a communications revolution, a cable connecting Europe to North America was a big deal, and, well, if I were running a company whose products revolved around interpersonal communication, I’d try to capitalize on it, too.

So, the tin remains a mystery, but here’s what I think it is: With the coming of trans-Atlantic communications, Cutter-Tower Company decided to capitalize on the new technology by branding one of their pens as the “Atlantic Cable” Pen, evoking the future of communications. Just as “HD” is used inappropriately or 7-segment displays were added to analog equipment to call them “digital”, piggybacking your product on the buzzwords of cutting-edge technology is a tried-and-true road to success. Had the 1857 attempt to run a cable succeeded, Cutter-Tower might have had a big-seller on their hands, but it was ten years before a cable made it from one end to the other intact. I’d also guess that the patent is on the unique and charming container design, but was displayed prominently to encourage the idea that somehow the Atlantic Cable Pen was a new technology. In the end, it was an average pen, needing new tips, and the tin, and all it’s fancy design, was to sell a rather commonplace pen to the masses.

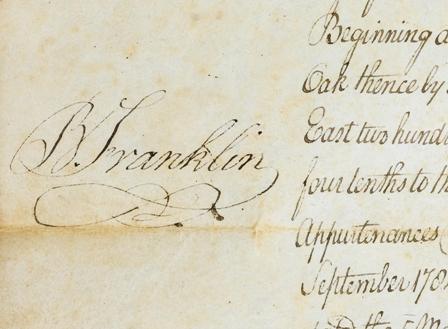

As a bonus, here’s what was inside:

This tin one belonged to Bessie Bayless, from Pennsylvania and Ohio. From the Atlantic telegraph lines, to Pennsylvania and Ohio, to the Fine Arts Club in Fargo, North Dakota, and finally into the hands of someone who obsesses over trivial mysteries, this tin is more than just a holder of nibs: it’s a world traveller and a mystery for the ages — and it’s mine.

This tin one belonged to Bessie Bayless, from Pennsylvania and Ohio. From the Atlantic telegraph lines, to Pennsylvania and Ohio, to the Fine Arts Club in Fargo, North Dakota, and finally into the hands of someone who obsesses over trivial mysteries, this tin is more than just a holder of nibs: it’s a world traveller and a mystery for the ages — and it’s mine.

About the most unique thing about this bill is that it’s a

About the most unique thing about this bill is that it’s a

Two designs were made of the Stella: a “flowing hair” version, like the one in the Stack’s Bowers auction, and the “coiled hair” design, which is rarer. The “flowing hair” Stella was designed by mint artist Charles E. Barber; the “coiled” by George T. Morgan. Both designs were quite similar, and both shared the same reverse. The reverse design is what gives the coin its name: the center of the coin is filled with a large star — a “stella” — thus giving the coin a casual name, like the “eagle” gold coins which came as portions of $10. Being worth $4 means it could be divided in fourths into smaller denominations, like a dollar and the $10 gold eagle were.

Two designs were made of the Stella: a “flowing hair” version, like the one in the Stack’s Bowers auction, and the “coiled hair” design, which is rarer. The “flowing hair” Stella was designed by mint artist Charles E. Barber; the “coiled” by George T. Morgan. Both designs were quite similar, and both shared the same reverse. The reverse design is what gives the coin its name: the center of the coin is filled with a large star — a “stella” — thus giving the coin a casual name, like the “eagle” gold coins which came as portions of $10. Being worth $4 means it could be divided in fourths into smaller denominations, like a dollar and the $10 gold eagle were.

Everyone was all abuzz about this fabled expert in strangeness, and I wasn’t one to disappoint. I picked up the little container, turned it around in my hands, slid the little door open and closed, and made my assessment.

Everyone was all abuzz about this fabled expert in strangeness, and I wasn’t one to disappoint. I picked up the little container, turned it around in my hands, slid the little door open and closed, and made my assessment.

This tin one belonged to Bessie Bayless, from Pennsylvania and Ohio. From the Atlantic telegraph lines, to Pennsylvania and Ohio, to the Fine Arts Club in Fargo, North Dakota, and finally into the hands of someone who obsesses over trivial mysteries, this tin is more than just a holder of nibs: it’s a world traveller and a mystery for the ages — and it’s mine.

This tin one belonged to Bessie Bayless, from Pennsylvania and Ohio. From the Atlantic telegraph lines, to Pennsylvania and Ohio, to the Fine Arts Club in Fargo, North Dakota, and finally into the hands of someone who obsesses over trivial mysteries, this tin is more than just a holder of nibs: it’s a world traveller and a mystery for the ages — and it’s mine.