Victorian Turn of the Century Cotton Batting Ornaments By lucysornaments; via fair-oaks-antiques.tumblr.com.

Author: Deanna

Sylvia Pope is a 70-year-old grandmother who loves Christmas

Her house in Morriston, Swansea, South Wales is home to her ever-growing collection of Christmas ornaments, which now numbers over 1800 pieces. The glittering holiday baubles come from all over the world and, because she has more than would fit on her Christmas tree, they hang from her living room ceiling for all to enjoy.

More photos & info if you click 😉

American Pickers (The Parody!)

Join Mike Woof and Frank Schnitz as they pick across America! Who knows, they might even make history… BLOOPERS! http://youtu.be/iSIn9KW96WI WIN PRIZES!

See on www.youtube.com

In 1913, She Told Him They Couldn’t Be Together. 100 Years Later, THIS Was Just Discovered.

While searching through the attic of his father’s house, a son came across boxes of old items. The most interesting were piles of love letters sent from a man named Max. From 1913-1978, Max and Pearle wrote each other. All his letters begin with “My Sweet Pearle” and end with “Forever yours, Max”. These letters were supposed to have been burned when Pearle passed away in 1980, but the family didn’t honor those wishes, and one of the greatest love stories began to unfold.

In 1911, a woman named Pearle Schwarz met a man named Maxwell Savelle at the Country Club. They fell madly in love. Unfortunately, Maxwell would not convert to Judaism (his parents were Southern Baptists) and so they could not be together. They went their separate ways – Maxwell went into the Navy and Pearle continued to pine for him until she died. She never let go.

See on www.viralnova.com

Load Up Your Vintage Sleighs

We’ve all seen those cute vintage Santa and reindeer sleigh sets…

And we’ve all seen enough of the old sleighs at thrift shops to know that eventually, like Santa’s sleigh Christmas morning, whatever goodies were originally in the sleigh have left — even Santa and his reindeer have departed leaving an empty and forlorn sleigh, just shadow of its former useful and joyful self.

But Wanda’s archive of Christmas decorating inspires me to rescue and adopt these old empty sleighs and fill them with other collectibles. (I do have quite a number of those just sitting around!) Here she shows some vintage plastic dolls of other nations taking a ride around the world in Santa’s sleigh.

And here, retro kitschy poodles pile on in! I just love that!

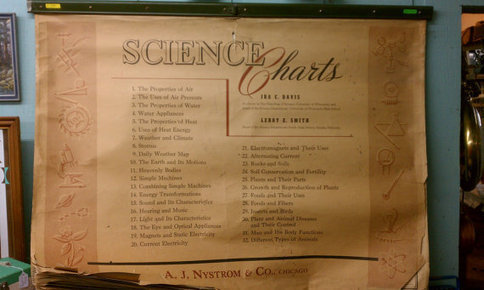

One Of A Kind 18 Page Vintage Science Chart Set by AJ Nystrom Flip Chart HUGE Like Pull Down School Map Illustrated Machines Biology Botony

A vintage set of Science Charts by A. J. Nystrom & Company of Chicago. The 18 pages are bound in a metal mounting — like those pull-down wall

Click for the fabuluos pics!

See on www.etsy.com

Vintage Embalming Fluid Crate

An old wooden crate that once held bottles of embalming fluid. I spotted it in an antique shop (and forgot I had on my camera lol). Printed on the side: Penetrating Beta-Dioxin Re-Concentrated Embalming Fluid.

Program teaches history via beloved quilter, ‘Pioneer Girl’ Grace Snyder

Grace Snyder’s lively eyes gaze out of her 1903 wedding photograph. There’s an astonishing hat atop her head and a tiny, cat-got-the-cream smile on her lips. She perches just behind her cowboy husband, her clasped hands resting near his left shoulder.

Her story, in many respects, mirrors Nebraska’s history in the late 19thcentury and much of the 20th century.

Born in 1882, reared in a sod house on a Custer County homestead and married to a Sandhills cowboy and rancher, she recounted her pioneer life in the 1963 book “No Time on My Hands,” as told to her daughter, author Nellie Snyder Yost.

Along the way, she became nationally known for her quilting expertise. Two of her quilts were designated as among the 100 best 20th-century quilts by Quilters Newsletter Magazine in 1999. She was named to the National Quilters Hall of Fame in 1980, two years before her death at 100.

Now Grace Snyder is the focal point of an innovative new history curriculum developed jointly by NET Learning Services, the International Quilt Study Center and Museum at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln and the Nebraska State Historical Society.

Called “Tiny Stitches, Big Life,” the online multimedia project uses Snyder’s quilts and her life experiences to bring pioneer history to life for Nebraska elementary school students. It is the first module of a larger project, “Stories of Nebraska Quilters,” with plans to develop additional material about other Nebraskans who are remembered through their quilts.

See on newsroom.unl.edu

Casual Vintage Holiday Table Centerpiece Using An Old Wooden Drawer

As I’ve said before, I like useful collectibles — and, because I don’t like anything to go to waste, I like to find new ways to make use of old things. Just because something is “old and just laying around,” doesn’t mean it can’t be salvaged or re-purposed. Like the vintage refrigerator crisper drawers, I knew these old wooden desk drawers I’d found could do something new and fabulous… Worn, paint-chippy wood is so charming!

Immediately, I thought of the holidays and the need for low centerpieces which wouldn’t get in the way of seeing family and friends.

I lined the drawer with this seasons’ hottest decorating fabric is burlap (probably because it is both rustic and natural looking for Fall), but you can use any fabric that goes best with your table settings. Inside, I placed some nested vintage brown glazed stoneware bowls, a vintage brown milk bottle, some little glass bottles with colorful rocks and shells, and then, for some extra seasonal flair, I tucked in some pheasant feathers. Pretty enough for a Thanksgiving table, don’t you think?

You can certainly fill the bowls with pine cones or something else decorative, or use the bowls to help with serving at the holiday table. And you sure can go crazy with red and green for Christmas; or change the colors and decorative combinations to match your china, your every day decor, whatever you’d like!

I may just keep this vintage wood drawer on the table top all the time. It can be awfully practical, serving to store the family’s usual table needs, such as napkins, salt and pepper shakers, the morning’s cereal bowls — whatever you find you need to leave on the table. And since it’s all in one drawer, you can pick it up as easily as any tray (maybe even more so, as the deeper sides mean less things will topple out and over!) to wipe the table clean, change the tablecloth, etc.

(See also Sit Down to Handmade Table Settings.)

Photos Reveal Harsh Detail Of Brazil’s History With Slavery – NPR (blog)

NPR (blog)

Photos Reveal Harsh Detail Of Brazil’s History With Slavery

NPR (blog)

Brazil was the last place in the Americas to abolish slavery — it didn’t happen until 1888 — and that meant that the final years of the practice were photographed.

Have you ever looked at your collection of photographs and noted what stories they tell and preserve?

See on www.npr.org

Lessons From The Maltese Falcon

You may have read the news about the titular movie prop from film noir classic The Maltese Falcon (1941) going up for auction — expected to fetch $1.5 million. The 50 pound falcon statue is valuable not only to those who love film or who are fans of Humphrey Bogart and Mary Astor, but to art lovers as well, for the prop was created by Fred Sexton.

Guernsey’s, the auction house behind the auction at New York City’s Arader Galleries, provides quite a lengthy piece on authentication of the film prop, which begins with this basic story:

The story of the Maltese Falcon statuette begins the same year the movie was filmed – 1941 – when Huston hired Los Angeles-based artist Fred Sexton to sculpt the prop for his directorial debut. Huston and Sexton were high school classmates and close friends, and the film director collected many of Sexton’s paintings.

In an on-camera interview with Vivian Sobchack in August 2013, Sexton’s daughter, Michele Fortier, discussed her father’s distinctive and familiar signature, and described her childhood experiences amongst Hollywood’s early elite and on movie sets.

Hank Risan owns two authenticated Maltese Falcon statuettes from the 1941 film production that bear Fred Sexton’s distinctive “F.S.” markings and they are widely regarded as two of the most valuable film props in the history of cinema. In 2004, UCLA Professor Richard Walter, a court-approved expert appraiser, supported the high valuations in an eloquent comparison to another highly-prized film prop: one of four pairs of ruby red slippers worn by Judy Garland in the iconic Wizard of Oz, which sold for $666,000 in 2001. “But whatever the slippers’ value,” Professor Walter wrote, “it has to be less than that of the falcons because the slippers are merely one prop, albeit an important one in the movie. The falcons on the other hand are the namesake props that define the picture itself. It is significant in the extreme that in addition to being important props they are also the title of the film.”

“Life imitates art,” stated Mr. Risan. “What’s amazing is that in the film Spade and Gutman discuss the value of the falcon in similar terms. The rara avis has a unique backstory as compelling off-screen as in the film. The black birds are truly objects d’art.”

However, in the auction held today, The Maltese Falcon did not fetch the predicted million dollars or more — in fact, it didn’t sell at all.

The official language for that is “passed” and it happens when the reserve price is not met. While the reserve may have been set too high, this can happen simply because everyone thought everyone else would be bidding and so they assumed they wouldn’t get it. Auctions are rather like elections that way; people stay home thinking everyone else is going to take care of business. But, be it auction or election, those who care ought to show up.

It remains to be seen how long it will take for this Maltese Falcon to show up at auction again.

7,500 Years Old “Toy Car” — The Earliest Evidence Of The Wheel

Author Cliff Dunning: “Historians tell us the oldest civilized cultures who developed the wheel are around 5,000 years old, and yet, new discoveries are continually pushing this date further back – WITHOUT our history books reflecting on the new information. Generations of people still believe that the oldest organized civilizations are those that lived in the Middle East, parts of China and groups scattered throughout the world. Before 3,000 years – we are told that man lived in caves. Here is an example of the wheel, attached to a small toy car of some type that was found to be 7,500 years old.

See on humansarefree.com

40 Gargoyles and Grotesques Around the World

In architecture, a gargoyle is a carved stone grotesque, usually made of granite, with a spout designed to convey water from a roof and away from the side of a building thereby preventing ra…

Whether you need to know the difference between gargoyles and grotesques, or just want eye-candy, click!

See on twistedsifter.com

View-Master Viewers

The following is a list of viewers produced from 1938 to 1996 and the “known” variations. Since many items are continually being “discovered” for the first time, any updates by our readers would be greatly appreciated. We are only listing production viewers.

A great timeline of View-Master viewers

See on www.cinti.net

Scotty The Pup Desk Accessory

You may have seen these vintage wire desk sets, but chances are you didn’t know they had a name — or at least you probably didn’t know their name. Like many vintage items are found without the boxes, it can be hard to find out the actual name of an item. Thankfully, I found this one boxed so I know this little guy is Scotty The Pup, aka Mac’s Dog.

His metal coil body holds letters, his coiled tail holds a pen (or pencil), and you can hang paperclips off his chin. These vintage doggy desk sets came in silver chrome, gold, and matte black finishes. I’ve got one silver, and one black one. The silver desk secretary doggie was an early one; the box is marked that the patent was applied for.

Vintage Coffee Advertising Piece

A lovely vintage advertising piece for Radiant Roast Coffee (Fairway Fine Foods, St. Paul, Minnesota, Fargo, North Dakota). This framed piece, likely used in stores, features three images of the coffee making process: Blending, Grinding, and Vacuum Packing. Spotted at Antiques On Broadway.

Fashion & Sewing Pattern History, Part Four

(You might want to catch up: Part One, Part Two, Part Three.)

By the start of the 1900s, home sewing and clothing patterns were big business. One of the last to enter the fray at the turn of this century, would become another one of the big names in sewing pattern collecting. According to Zuelia Ann Hurt in Craft Tools — Then and Now (Decorating & Craft Ideas, October 1980 issue):

Soon after 1900 a prominent fashion magazine called Vogue published a coupon for a pattern. For fifty cents, the reader received a pattern hand-cut by the designer Mrs. Payne on her dining-room table.

While Vogue was using its publishing power to spawn a fashion pattern business, the other sewing pattern companies did not slow down. Here are some notable moments — and collectible names — in sewing pattern history.

In 1902, James McCall’s The Queen of Fashion magazine changed its name again and became McCall’s Magazine, widening the contents of the publication to other womanly pursuits and interests.

In 1910, Butterick continued their sewing pattern industry innovation by introducing the “deltor” — the first instructions printed on a sheet included inside the pattern’s envelope.

In 1914, the Vogue pattern department officially left the magazine to become Vogue Pattern Company. (This was in no small part due to the 1909 purchase of Vogue by Condé Nast.) Vogue patterns continued to be sold by mail until 1917, when B. Altman’s department store in New York City became the first store to stock their patterns. In May of 1920, Vogue Patterns launches the Vogue Pattern Book.

In 1920, there was another major change in the sewing pattern industry. This time it was McCall’s leading the way by moving from the perforated tissue patterns to printed ones. Eventually the others would follow suit. McCall’s would also begin working with designers like Lanvin, Mainbocher, Patou, and Schiaparelli.

An advertising salesman for fashion magazine Fashionable Dress, Joseph M. Shapiro, was shocked to find that something consisting mainly of tissue paper would cost $1. Via his connections, he found the way to produce — and profit from — a pattern which would sell for just 15 cents. The Simplicity Pattern Company was born in 1927 and Joseph’s son, James J. Shapiro, was its first president. With such a low price, Simplicity expanded quickly, including internationally.

In 1931, Vogue starts Couturier Line and introduces new large format envelopes.

In 1931, Simplicity began producing DuBarry patterns exclusively for F. W. Woolworth Company (through 1940).

In 1932, Condé Nast starts the Hollywood Pattern Company. Hollywood Patterns featured designs straight of film and usually had photos of Hollywood stars on the packaging as well. The Hollywood Pattern Company ceased pattern production a few years after the end of World War II.

Also in 1932, McCall’s would again push the envelope by, well, pushing the envelope — now full-color illustrations appeared on the covers of McCall’s pattern envelopes.

In 1933, Advance began manufacturing patterns sold exclusively at (and for) the J. C. Penney Company. Because of the J.C. Penny connection, Advance was able to secure a number of designers (including Edith Head and Anne Fogarty) as well as rights from Mattel for authentic Barbie fashion patterns. (The company was sold to Puritan Fashions in 1966.)

In 1946, Simplicity finally fully converts from perforated patterns to printed sewing patterns.

In 1949, Vogue added the Paris Original Models patterns from French Couturiers and was the only company authorized to duplicate these fantastic designs. Such deals with international designers would expand, including millinery designs in 1953 and International Designer Patterns in 1956.

In the 1950s, McCall’s patterns produces another designer line which included French couturier Hubert de Givenchy and Emilio Pucci.

In 1958, Vogue Patterns fully transitions from perforated to printed tissue patterns.

In the 1960s, McCall’s “New York Designers’ Collection Plus” featured designs from Pauline Trigere and Geoffrey Beene, among others.

Starting in 1960s and continuing through 1970s, Butterick produces the “Young Designer” series, featuring designs by Betsey Johnson, John Kloss, and Mary Quant.

In 1961, Butterick licensed the Vogue name and began to produce patterns under the Vogue name.

Images: Vogue Spring, 1916, via hampshire-estate-finds; vintage McCall’s printed pattern via misslacyg; Vintage Hollywood Sewing Pattern # 747 featuring Betty Grable, via ohiochestnutt; and Vogue Paris Original pattern by Nina Ricci via dalejeri.

Fashion & Sewing Pattern History, Part Three

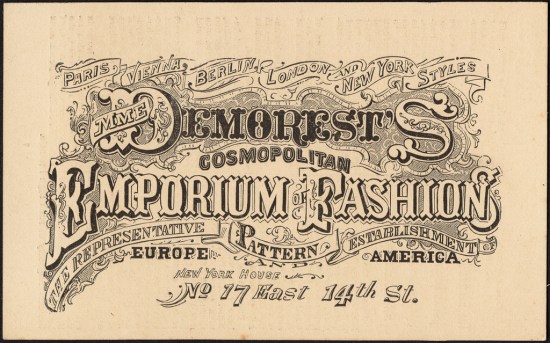

As you may recall from part two, fashion sewing patterns were still rather complicated in the mid-1800s. However, some, like Ellen Louise Demorest and her husband William Jennings Demorest, began to assist those who were interested in sewing at home — assisting at a profit, of course.

By 1860, Madame Demorest’s Emporium of Fashion began advertising her patterns in magazines. This was still by-hand work, with the patterns cut to shape in two options for the consumer: purchased “flat”, which was the cut patterns folded and mailed, or, for an additional charge, “made up” which had the pattern pieces tacked into position and mailed. At this time, Madame Demorest’s Emporium of Fashion used fashion shows held in homes, along with trade cards, to promote her patterns — as well Demorest publications. In 1860, the Demorests began publishing Madame Demorest’s Mirror of Fashions, a quarterly which not only featured plates of their own dress patterns but included a pattern stapled to the inside as well. However, patterns were still only available in one size at this time.

The beginning of sewing patterns as most of us know them has its roots in the winter of 1863. According to The Legend, Ellen Buttrick and her complaint were the mother of invention; but it was her husband, Ebenezer Butterick, an inventor and former tailor, who revolutionized sewing patterns and fashion history in the winter of 1863.

Snowflakes drifted silently past the windowpane covering the hamlet of Sterling, Massachusetts in a blanket of white. Ellen Butterick brought out her sewing basket and spread out the contents on the big, round dining room table. From a piece of sky blue gingham, she was fashioning a dress for her baby son Howard. Carefully, she laid out her fabric, and using wax chalk, began drawing her design.

Later that evening, Ellen remarked to her husband, a tailor, how much easier it would be if she had a pattern to go by that was the same size as her son. There were patterns that people could use as a guide, but they came in one size. The sewer had to grade (enlarge or reduce) the pattern to the size that was needed. Ebenezer considered her idea: graded patterns. The idea of patterns coming in sizes was revolutionary.

By spring of the following year, Butterick had produced and graded enough patterns to package them in boxes of 100, selling them to tailors and dressmakers. These early Butterick patterns were created from cardboard. However, as most early patterns were sold by mail, heavy cardboard was not ideal for folding and shipping. Butterick experimented with other papers, including lithographed posters (printed by Currier and Ives). While these were easier to fold and ship than cardboard, they were still not ideal. Ultimately the search lead to less expensive and light-weight tissue paper.

For the first three years, Butterick patterns were for clothing for men and boys; in 1866, Butterick began making women’s dress patterns. This is when the sewing pattern business really began to grow. In order to promote the mail order patterns, Butterick began publishing The Ladies Quarterly of Broadway Fashions (1867) and the monthly Metropolitan (1868).

Madame Demorest’s Emporium of Fashion was still going strong, as was their publication. Although the magazine was expanded to include a lot more magazine content as Demorest’s Illustrated Monthly Magazine and Madame Demorests Mirror of Fashions in 1864. In 1865, the name was changed again, this time to Demorest’s Monthly Magazine and Demorest’s Mirror of Fashions — more commonly referred to as Demorest’s Monthly. This monthly was reaching over 100,000 readers.

The success of sewing patterns could not be ignored and the competition would really begin; by 1869, James McCall started his pattern business.

These early sewing patterns by Butterick, McCall’s, and Demorest were not printed, but rather outlined on the tissue paper by a series of perforated holes. They were typically sent in an envelope which had a sketch of the finished garment and brief instructions printed on it. These instructions included suitable fabric suggestions, size information, and a description of how the pieces were to be cut from the tissue and pieced together to form the garment (assisted by a code of shapes, such as v-shaped notches, circles, and squares, which were cut into the paper).

In 1872, Butterick began publishing The Delineator. As with the earlier publications, The Delineator was originally intended simply to market Butterick patterns. However, it quickly expanded into a general interest magazine for women in the home, offering everything from fashion to fiction from housekeeping to social crusading (including lobbying for women’s suffrage in the early 1900s). As readership skyrocketed, the earlier publications were folded into The Delineator — and the magazine would go on to become one of the “Big Six” ladies magazines in the USA.

In 1873, McCall’s would start their own publication called The Queen. In 1896, the name was changed to The Queen of Fashion and it would be the first magazine to use photographs on its cover.

In 1875, the first in-store sewing pattern catalogs appeared. These were produced by Butterick.

Madame Demorest was still around. In addition to marketing paper patterns through the magazines, the patterns were sold through a nationwide network of shops called Madame Demorest’s Magasins des Modes. In addition to the paper patterns and drafting systems, the shops sold ready-made fashion items, Demorest’s line of cosmetics and perfumes, and custom dressmaking services to wealthy clients. It was the latter, along with fashion exhibitions in London and Paris, which really boosted the designer and therefore the company’s profile. By the mid-1870s, there were 300 Demorest shops, employing 1,500 sales agents. Her employees were mainly women, including African-American women who received the same treatment as the white women workers.

In 1877, business was peaking. The Demorest’s Monthly began circulation in London and, along with the quarterly, the company began publishing Madame Demorest’s What to Wear and How to Make It. Just a few years later, however, Demorest business declined. This was unfortunately do to the Demorests’ failure to patent their patterns, allowing themselves to be bested by competition. In 1887, Demorest sold their pattern business, which went on to live on primarily in name only — including sewing machines.

To Be Continued…

Image of Mme. Demorest Hilda Polonaise Pattern via dakotanyankee; image of 1899 Butterick Pattern Ladies Double Breasted Coat via janyce_hill.

Fashion & Sewing Pattern History, Part Two

As we left things at the end of part one, we were moving into the early 19th century and taking a closer look at how clothing pattern history closely parallels domestic sewing machine history.

In the early 19th century, sewing machines were not only impractical and complicated, but seen as threats. In 1830, for example, another French tailor, Barthelemy Thimonnier, found himself thwarted by another group of French tailors — this time, the tailors were so fearful of unemployment that they burned down Thimonnier’s garment factory. Four years later, American Walter Hunt would build a sewing machine; but he did not follow through on the patenting of his invention because he too feared his invention would cause unemployment. Early 19th century paper patterns, while apparently less economically feared than sewing machines, were so complicated and off-putting as to be considered fearful themselves.

These early 19th century patterns had all the pieces of a garment superimposed on one large sheet of paper. This meant that each piece was coded with specific lines, in different patterns (straight lines, dotted lines, scalloped lines, broken dash-like lines, and even combinations of these; sometimes all in the same color). To make matters worse, multiple garments were often on the same page! To make use of this map of crisscrossed patterned lines, one had to place a plain piece of paper beneath the paper pattern and use a tracing wheel to follow the (hopefully correct!) lines to make a separate pattern for each pattern piece. Even after all of this, the person attempting to make the garment was still not done. As these patterns were sold in a “one size fits all” sort of mentality, it was up to the seamstress or housewife to measure and grade (enlarge or reduce) each piece to fit the individual who would be wearing the garment. Make any mistakes along the way, and you would have wasted the fabric and your time. Perhaps ruined the pattern as well. No wonder these early sewing patterns weren’t wildly popular.

(Photo of uncut paper patterns above from Journal des Demoiselles, with illustrations, via Whitaker Auction Co. These items are part of the Fall Couture & Textile Auction to be held November 1 – 2, 2013; auction estimate value of $100-$200.)

However, by the 1850s, sewing machines would go into mass production for domestic use. To say that sewing machines became popular for home use is an understatement; between 1854 and 1867 alone, inventor Elias Howe earned close to two million dollars from his sewing machine patent royalties. (Isaac Singer built the first commercially successful sewing machine, but had to pay Howe royalties on his patent starting in 1854.) Like computers and the Internet today, those who purchased sewing machines for use in the home found themselves dedicated to putting them to use. In Victorian London’s Middle-class Housewife: What She Did All Day, Yaffa Draznin writes:

The housewife with free time in the afternoon was far more likely to spend it at the family sewing machine than in making social calls. For the first time, it was possible to make a man’s shirt in just over an hour where before it would have taken 14 1/2 hours by hand; or to make herself a chemise in less than an hour instead of the 10 1/2 hour hand-sewing job. No wonder the middle-class married woman welcomes the domestic sewing machine with such enthusiasm!

…However, considering how complicated fashionable dresses for women were, it is probable that most housewives, even those who had to watch their expenditures, did not have the talent for mastering complex dress construction; they would continue to call in a dressmaker for their more elaborate clothing. Still, sewing on a machine, like the art of cooking, was a learned skill that gave the middle-class matron both pleasure and a feeling of professional competence — job satisfaction in a sphere where a sense of inadequacy was too often the norm.

No doubt this was all equally true of women in America too.

While the upper classes may have frowned upon use of the sewing machine (for everything from the potential decline in the art of hand-stitching to the encroachment upon upper-class fashion looks), and purse-string-controlling husbands may have resisted investing in arguably the the first labor-saving device for the home (why would any self-respecting husband spend money on something his mother had done for free — besides, women were incapable of operating complex machinery!), middle-class women themselves ushered in the era of the sewing machine. With a little help from Isaac Singer.

Singer’s first consumer or domestic sewing machine, the Turtle Back (named for the large container the machine came in), sold for $125 — at a time when the average household income for a year was $500. To overcome objections, Singer introduced America and the rest of the world to installment payments. The marketing combination of “small monthly payments” along with demonstrations offering free instruction with each machine proved irresistible.

This, of course, could not go unnoticed by the ladies magazines and household manuals of the day. These publications began to include long and detailed sections on home dressmaking, covering everything from measurement taking to advice on fitting garments. And, of course, on patterns themselves. Soon, these magazines began to print dress patterns inside their pages. Such “free” patterns made for great promotions; it drew women to purchase and subscribe to the magazines and no doubt sold advertising space as well. But still, these were those complicated types of sewing patterns…

To Be Continued.

Fashion & Sewing Pattern History, Part One

While sewing itself dates back thousands of years, to the Paleolithic period, patterns for making clothing are a much more modern invention.

The earliest known fashion patterns, dating to ancient Egypt, were relatively simple guide templates cut from slate. (Similar slate guides, presumed to the products of trade, have also been found in ancient Roman catacombs.) However, for the most part early human history, clothing was primarily constructed from rectangular shaped pieces of uncut woven fabric. The fabric, so labor intensive to produce and therefore costly to purchase, was primarily left intact to minimize waste. At this time, the wearer was almost always the maker of his own clothes. The cloth itself, not the shape or design of the garment, was the distinguishing feature.

However, by the year 1297 the first reference to the word “tailor” is used in Europe. This would indicate that pattern making must have begun at some point prior, as tailoring involves the acts (or arts) of cutting and sewing cloth — the two basic aspects of constructing clothing from a pattern. Also in the 13th century, a French tailor attempted to make patterns from thin pieces of wood. However, this tailor’s invention was thwarted by the powerful Tailor’s Guild whose members feared such an invention would put them out of business.

According to Principles of Flat Pattern Design by Nora MacDonald, the real art of pattern making wouldn’t begin until the 15th century. This is the result of two pivotal historical moments: the Renaissance, and the movement’s desire to dress to accentuate the human form, and Gutenberg’s printing press. The former meant that carefully engineered pieces of fabric were cut to form clothing which would contour to the body. The latter meant that images of clothing designs could be more widely disseminated. So, now when the wealthy had their new form-fitting frocks, the little people could all see images of them — even if they had never been to the big cities, let alone court. As countries grew in power (first Italy, then Spain and France), so they influenced others. And what they were wearing was a large part of that influence. Fashion was truly born.

The fashions of these times continued to be made by tailors. The process was elaborate, with tailors working with each client’s to take their individual measurements to customize and even create patterns. Such highly revered skills meant that the services of tailors were relegated only to the very rich. This continued to be the case through the Industrial Revolution.

For those who could not afford a tailor of their own, staying fashionable was laborious. While the publications of the day (such as Godey’s Lady’s Book & Magazine, The Young Ladies Journal, and Peterson’s Ladies National Magazine), depicted the latest fashion designs, the accompanying text was more like a flowery description than a set of step-by-step instructions. Your average household, relying upon the lady of the house and her daughter(s) to make the clothing, struggled to make use of the fashion lithographs provided. Rarely were diagrams provided; and no measurements were given. Even when one was talented enough to make the required calculations, all the sewing was done by hand — and the sewing was typically done after more vital and immediate work was performed. By the time your dress was finished, it really could be out of fashion.

The Industrial Revolution brought along a host of advances which greatly increased the standard of living for “the masses”. This included less expensive textiles and an even greater desire for fashions — naturally spurring advances in the fashion industry. As we reach the early 19th century, clothing pattern history closely parallels domestic sewing machine history.

Welcome to Leila’s Hair Museum

The ONLY hair museum in the world with hundreds of wreaths and thousands of jewelry pieces made from human hair. The Hair jewelry was worn both by men and women of the Victorian period (1800 – 1900) and earlier.

See on www.leilashairmuseum.net